Fundamentals: Tax Rates

This article is part of a continuing series on fundamentals of financial planning.

Taxes are complicated. But understanding and taking action on just a few tax concepts can make a big difference. One of them is marginal tax rates, also called tax brackets.

We’re looking at the federal income tax only.

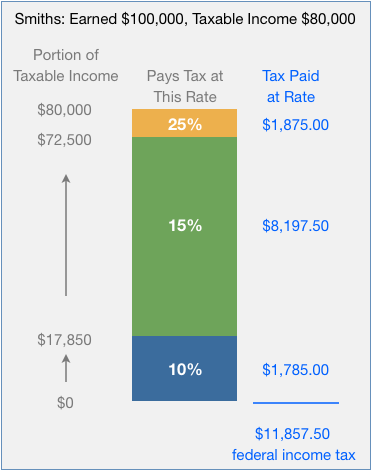

John and Mary Smith are our sample tax-paying couple. (Married filing jointly, no dependents, standard deduction, for simplicity.) The Smiths both work and had combined income of exactly $100,000 in 2013. After exemptions and the standard deduction, they have taxable income of $80,000.

The Smiths are in the 25% tax bracket.

The Smiths are NOT paying 25% tax on their taxable income of $80,000. They are NOT paying $20,000 in tax. They ARE paying $11,857.50, which is 11.86% of their $100,000 earnings.

How?

First, their income of $100,000 was reduced to $80,000 of taxable income by exemptions and deductions.

Second, the marginal rates (brackets) tax portions of their income at different rates: first at 10%, then at 15%, finally at 25%.

Here’s a chart of the brackets that apply to the Smiths:

Most of the Smiths’ taxable income is at the 15% rate. The highest rate is 25%, called the marginal rate. But their overall tax compared to their $100,000 earnings is about 11.86%

Most of the Smiths’ taxable income is at the 15% rate. The highest rate is 25%, called the marginal rate. But their overall tax compared to their $100,000 earnings is about 11.86%

Question: If Mary had received an additional $1000 bonus right at the end of 2013, how much tax would she pay on that?

Answer: $250. That additional $1000 falls in the highest bracket, the marginal rate, 25%. So she’s taxed at the highest rate for that additional income. That’s how marginal brackets work.

Question: If John and Mary decided to contribute an additional $1,000 to their retirement savings account in 2013, how much tax would they save?

Answer: $250. Why? Retirement contributions generally* reduce your taxable income, in this case from $80,000 to $79,000. They reduced the portion of their taxable income being taxed at the marginal rate of 25%. So that $1000 contribution really only “cost” them $750 now because they saved $250 of tax.

Marginal rates are an important concept both on additional income and reductions to taxable income. That’s why using retirement savings accounts can mean big savings in taxes now.

*There are limits and rules for contributions to tax-deferred savings accounts.

Important: This article is of a general educational nature, simplified to illustrate concepts; it is not tax advice. See your tax professional for your specific situation. Tax-deferred retirement accounts are generally subject to tax when money is withdrawn. At that time, tax rates could be higher or lower than when working.